Good learning resources are hard to find. Especially if you’re seeking free content. The internet is filled with content creators, all looking to grab your attention.

As an entrepreneur, I’m fond of collecting and sorting resources. I want to focus my time and my mind on courses that are worth the investment. Although we love long lists of links, we often end up skimming through them. We add a few to our favorites and never check them again.

I like to approach things the other way around: I filter lists of websites and books down 1 or 2 sources that feel deep, accessible and efficient. And I stick to them. I prefer a single book like Jesse Schell’s Art of Game Design over a list of 50 random websites. I’d rather explore a single library like Ctrl-paint rather than watch dozens of cheap Gumroad trainings. I want well-written and energizing courses. I want dense content and authors that I can trust. And I’m sure you do too! This article is here to answer this desire.

To prepare this list, I dug through numerous websites. I drew from countless hours spent looking for resources in the past to bring you the best, free online resources I could find and be recommended. The list is not exhaustive, and not meant to be exhaustive. But it will still keep you fed with valuable information for months!

You will find some popular resources in here, some that you may know very well. But you’d be surprised to see how many fellow developers don’t! To please everyone, I did my best to mix well-known websites with some less common ones. They are organized in categories, each featuring a handful of entries. I also took the word “developer” in the broad sense here.

Game Design

1. The GDCVault’s free section (Video) contains many talks from the Game Developer Conference itself. There, you can find some of the best insights on game creation from some of the most experienced or popular developers in the gaming industry. While Gamasutra offers text-based content for those who prefer that, the GDC vault is focused on videos and slides. Note that the GDC vault is being archived on its new Youtube channel. With a few videos released every week, this is a great place to discover fresh talks from the industry leaders.

2. Pixel Prospector is a reference as far as game creation resources are concerned. This website offers a complete, free guide to marketing your game, as well as long lists of finely categorized resources. From the same author, you can find The Big List of Youtubers. Is is a list of content creators who cover video games classified by their spoken language and preferred genres. You can also find multiple lists of video game journalists on PixelProspector’s VideoGameJournaliser.

3. Extra Credits (Video) is a popular YouTube channel filled with short, specific videos about game design. It also features game recommendations and pleasant history lectures (soon on Khan Academy). The content is insightful and tends to follow the gaming industry’s news stories. Because of that, Extra Credits is a great place to get a quick sense of how the game creation world is evolving.

4. Three Hundred Mechanics is a neat pick shared by a developer friend. The author, Sean Howard, went on a quest to design and write 300 game concepts. In each entry, he documents his ideas and sometimes algorithms or his design process. His website explores numerous ideas and genres, and is quite inspiring. The mechanics exposed there feel pretty original overall. I especially dig the procedural category, as it’s usually hard to find content in that domain. A companion website called Three Hundred Prototypes features a few HTML5 test games that correspond to some of those concepts.

5. Donjon is more of a niche entry. It is both a playful and a useful website for RPG creators out there. It contains a variety of specialized text and value generators to release you from your creative block. You… can create dungeons, shops with randomized descriptions and locations, get lists of names, calendarsyou name it. Donjon even offers specific tools for fantasy games, Dungeon and Dragon inspired games, and sci-fi universes. Although it’s probably meant for tabletop game players initially, it is always useful if you’re working on an RPG.

The next entry is for lovers of the platform genre out there.

6. Scroll Back: The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers is a Gamasutra article that breaks down elements of a controller’s design for a platforming, side-scrolling game. It offers a deep analysis of the implementation of player controls. It talks about specific techniques to achieve a tight feel. It is not a very long paper, but it is one of a kind I wish I would see more often.

Development

As a rookie programmer myself, so I had to ask experienced, trustworthy teammate for help here.

7. Game Programming Patterns is a free book, as in free beer. It covers a variety of common programming patterns, all applied to game creation. Each and every chapter covers one common pattern, and starts with a concrete example. That’s probably the best part of the book: it always illustrates why a pattern is worth knowing. The author also outlines the limits of a variety of patterns, how they evolved over time, etc. the code examples are written in C++, but are always short and simple to read. Cherry on the cake: a column on the right of each page contains complementary comments to fill any gap the original book might have had.

8. The Ludum Dare is not a learning resource in itself. You probably know it already: it’s a website where very popular game jams are organized multiple times a year. It’s a great exercise, a great experience, but not a free resource in itself. So what is it doing in this list? Think about it: the source code and assets of every game submitted for the main events is available. For instance, you can learn how to structure Haxe code for a game by looking at Deepnight’s lovely creations. Each event comes with its lot of fresh game concepts, and you can learn how each of them was implemented by looking at the sources.

9. The Github Education Pack is a special element in this list, as it’s only relevant to students. It features a variety of normally paid services for developers, offered for free to anyone with a school-issued email address and a valid student ID card. It is worth a lot of money and contains some great, popular plans and services like some cloud hosting, private repositories on GitHub, etc. So if you know some students who could benefit from this, be sure to spread the word!

Digital Art

10. Ctrlpaint.com (Video) offers a full digital art curriculum for free. We are talking of more than 200, free, 5 minute long videos packed with information! Its author, Matt Kohr, is a freelance concept artist working in the entertainment/game industry. So he knows what he’s talking about, and he definitely is a talented teacher.

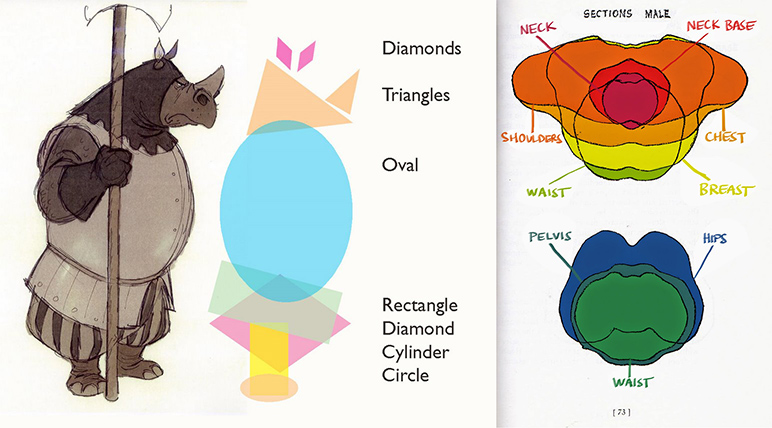

11. Proko (Video) is a YouTube channel dedicated to the study of the human body and drawing techniques. For aspiring concept artists, art students and other game artists, this is a great place to expand your understanding of the human body. Proko’s videos are beautifully edited and sometimes even feature animations to make their point crystal-clear.

12. 2d Game Art Guru is a blog maintained by Chris Hildenbrand, a senior game artist, with 20 years of experience using vector drawing software. “Life is too short to make bad art“, says the subtitle. Chris creates easy to follow game art tutorials designed with programmers and other non-artists in mind. Animation, vector drawing, game asset modularity… The articles cover a wide range of techniques to make your life easier as an artist. Chris’s latest tutorials are based on the open source tool Inkscape, which offers a rich feature set and is free to use.

13. GDquest or GameDesignQuest (Video) is a YouTube channel mainly dedicated to game art and game creation. It is meant to close the gap between the textual focus of 2d Game Art Guru and the concept art focused Ctrlpaint. There, you will find about 30 polished video tutorials, with one more coming out every week. So far, the channel has been focusing on 2d game art, but it does feature some videos and insights about game design. One new tutorial comes out every Thursday, in English and French.

14. Technical Art: Game art Tricks is a compilation of technical game art analyses. With rendering and assets production tricks pulled from Blizzard’s Diablo 3, Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed 3 or even Edmund McMillen’s The Binding of Isaac, the guides approach all sorts of techniques, games and genres. Ever wondered how parallax was handled in Don’t Starve? Or how 2K games faked the renderer of the inside of a room on their windows in Bioshock Infinite? This website has the solution explained and illustrated for you.

15. Android Arts is an archive of articles written by Niklas Jansson, a talented Sweden artist. The very first one you’ll stumble upon arriving on the page alone is worth reading. It’s a list of tricks and principles to get a better hang of art. Aside from that, Niklas shares notes about his artistic journey on his website. Although his writings can feel a bit all over the place, his pages are filled with images that depict his design thought process in great details. It is some form of indirect resource.

Storytelling

16. Seven Camels, or the Temple of the 7 Golden Camels is actually a blog maintained by the storyboard artist Mark Kennedy, a man known for his work on Disney’s Frozen, Raiponce and Tarzan. Since 2006, he shares all his knowledge about visual storytelling on his blog. His posts are filled with images and broken down into small, informative paragraphs. He analyzes scenes from movies, covers fundamental concepts of design and staging… If you want to create good visual compositions or stories for your games, this blog is an exceptional reference.

17. The Writer’s Journey is one of the greatest classics as far as storytelling is concerned. In this textbook, Christopher Vogler expands on Joseph Campbell’s popular The Hero with a Thousand Faces and tries to show that most stories tend to follow a similar broad structure. If you’re just interested in getting a sense of his theory, the author initially wrote a practical guide for Disney employees. You can read it for free on his website: A Practical Guide to Joseph Cambell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

References

Be it pictures or information, we need good references to design games. For the latter, we at least all know Wikipedia. As it turns out though, good reference photos are not only and slow to collect: they are hard to find. So here are a few places to get great ones.

18. The Reddit SWF Porn Network is not what its name might suggest. It is an organized network of sub-reddits dedicated to sharing beautiful pictures on specific topics. It is an outstanding place to discover new places, animal species and other design ideas.

19. Creative Uncut is a website that collects artworks from a wide variety of console and desktop games. The pictures are provided watermark-free. You can find some beautiful illustrations from Odin Sphere, Breath of Fire V or even the upcoming Dark Souls III.

General Knowledge

There is more to game creation than game design, programming and art. Much more. Some math skills are always interesting to have. You may need to learn a new language to communicate with your audience or to reach a new market. General knowledge expands our mental library, which we draw from all the time to produce new ideas. To round out this list, here are 2 links to teach yourself a bit of everything, online, for free. I’m leaving the filtering work to you on this topic.

20. The No Excuse List provides website recommendations to learn music, languages, programming… all sorts of things, for free. It features entries like Coursera or Khan Academy, 2 of my favorite places for free education.

21. The University of Reddit is another place to find free courses on a wide variety of topics. Social sciences, games, computer science, philosophy… the posts are categorized, and the social network’s voting system helps to find popular lectures.

Summary

Now, you should have enough content to keep you busy studying the art of game creation. Did we miss any of your favorite free learning resources? Do not hesitate to share them with us on twitter!

21 Free Learning Resources for Game Developers – GameAnalytics.

You must be logged in to post a comment.